On 24 July 2020, England became the fifth nation to make it compulsory for people to wear face coverings in shops in an effort to limit the spread of Covid-19. Thomas Parker looks at the two predominant types of medical face masks on the market, and the regulations that dictate how they are made.

On 5 June 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) updated its advice on medical and non-medical face masks.

The WHO recommended that non-medical masks should be worn by everyone in public spaces – such as shops, work, or social gatherings – and in closed settings like schools.

Their suggested use also includes people living in cramped conditions and those travelling on public transport.

The organisation does not, however, recommend the public use medical-grade masks, as these should be reserved for healthcare professionals and people in at-risk groups.

In March 2020, the WHO estimated that about 89 million medical face masks are required each month.

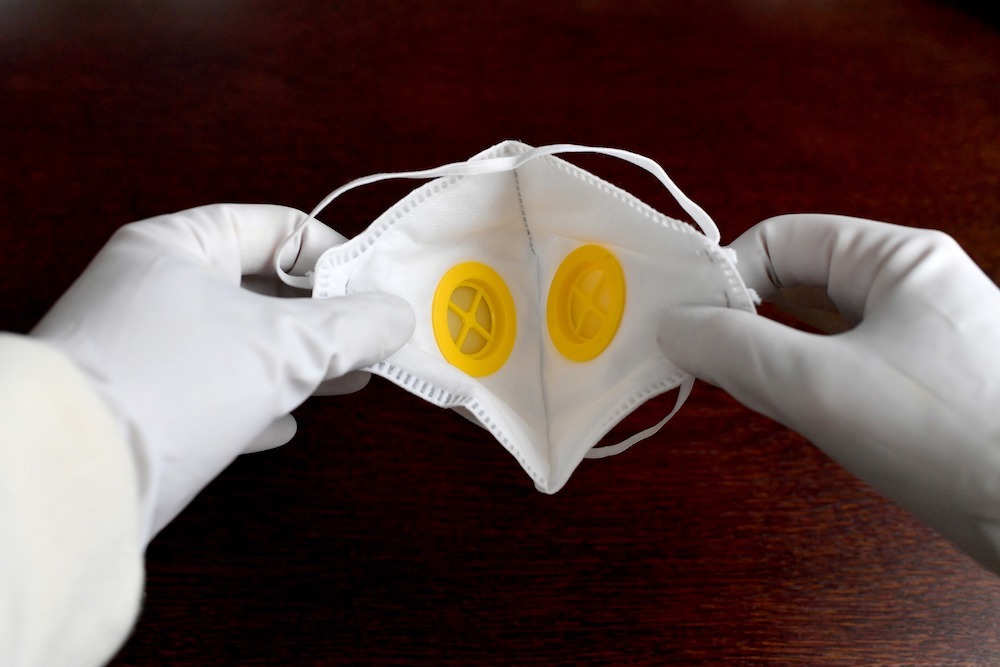

Face masks typically fall into one of two categories — surgical or respirator. Both variants are designed to offer various levels of protection against the transmission of bacteria.

Matthieu Menut, European Proxima preventative care division director of healthcare company Medline Industries, explains the difference is that surgical masks “provide sufficient protection when people are in direct contact”.

“For example, if an individual was face-to-face with someone, a surgical face mask would do a good job.

“If a person was, however, in contact all day long with people who have definitely got coronavirus, I think respirator masks for the likes of healthcare professionals makes more sense.”

Although both face mask types are designed to protect against the transmission of bacteria, they fall under different regulatory scrutiny.

Respirator masks are considered personal protective equipment (PPE) products by both the European Union and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), while surgical face masks are classified as a medical device.

In the EU, medical devices are split into one of four classes — I, IIa, IIb and III — with Class III devices being the most stringently assessed.

For sales on the European market, all products are required to hold a CE mark.

Although surgical face masks are considered a Class I medical device, they still have to undertake several tests to be certified.

These include how efficiently the masks filter out bacteria — with the devices also needing to be breathable, splash-resistant and complete a microbial cleanliness test.

Similar examinations are carried out by the FDA for businesses looking to sell surgical face masks in the US — with the authority also looking at a device’s particle filtration efficiency, alongside conducting a fire test.

Explaining the regulations for surgical face masks, Menut says: “It’s about finding the right balance between the highest filtration for the bacteria, and in the meantime, the comfort of breathing through it all day long.

“So you need to find the right balance between comfort and performance.”

To provide the most efficient filtration of bacteria, most face mask developers use either celluloid or polypropylene plastic fabrics.

Due to the simplicity of the design, surgical masks are simple to upscale and mass produce, although it takes a long time to certify a design.

Traditional surgical face mask manufacturers, such as 3M and Medline, have significantly upscaled their production of the device.

Businesses in the fashion and automotive industries are also helping by developing surgical face masks.

The FDA still recommends healthcare professionals use FDA-cleared products, although products that don’t have its device marketing authorisation can be used.

Alongside this, the WHO says surgical face masks are not required for members of the general public without respiratory symptoms, because there’s no evidence on its usefulness to protect those without the virus.

Unlike surgical face masks, respirator masks are regulated as PPE. In Europe, the masks are split into three filtering face piece (FFP) protection categories: FFP1, FFP2 and FFP3, with the latter conforming to the highest standards.

The category awarded depends on how much protection from outside substances is provided.

Most respirator masks used by healthcare professionals are ranked at either FFP2 or FFP3.

Menut explains: “The reason why these masks are considered PPE equipment is the shape of the mask — it covers a person’s face really well and is supposed to be sealed all around the nose and mouth.”

For a respirator mask to be approved, it has to go through what is often called the seal test.

This involves one person wearing the mask, while someone else sprays it, with the amount of ingress being measured.

Menut adds: “The mask has to be completely sealed from the external environment, and that’s the biggest difference between surgical and respirator masks.”

Respirator masks are commonly referred to as N95 — named as such because they block at least 95% of small micron test particles.

Alongside healthcare, these masks are used in construction, painting and mining sectors.

In the US, all such masks must be approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

Alison Casey, a medical devices analyst at market research company GlobalData, adds: “A subset of N95 masks are also approved by the FDA — and these are used by healthcare institutions.

“This second approval process has got less to do with the resource because all of them have a certain grade of filtration — it looks more at how tightly it fits to someone’s face.”

In the wake of the pandemic, the FDA has introduced an emergency use authorisation, which means all NIOSH-approved N95 respirators can be used by healthcare institutions.

The regulator has also said masks with approval in other countries, such as China’s KN95, can be imported and used by healthcare workers in the US.